Influence & Insight | October 2025

Leadership Story | Leaders Understand Well-Being

In a recent Wall Street Journal (WSJ) article titled The Rush to Return to the Office Is Stalling (behind paywall):

https://www.wsj.com/lifestyle/workplace/return-to-office-workers-fail-3d966807?mod=hp_lead_pos1

Author Theo Francis shares that companies Microsoft, Paramount and others are stepping up calls to get back to the workplace. Many of their employees are still phoning it in.

Francis continues:

Even as corporate bosses cut back on remote work and ratchet up in-office mandates, average office attendance has barely budged across U.S. workplaces. Companies are struggling to enforce mandates, and many managers tasked with herding folks into the office would rather not be there either. Other executives have made their peace with hybrid work, especially amid cooling consumer confidence and an unpredictable trade war.

“There’s a lot more pressing things for companies to be worrying about right now,”

said Beth Steinberg, a longtime tech-industry human-resources executive. As for whether bosses are cracking down on no-shows? “I haven’t heard of many consequences for that, especially if somebody’s a high-performer.”

These large company managers may wish to read Mark Crowley’s The Power of Employee Well-Being (review follows). Crowley’s new book is an intentional pivot toward elevating well-being that will help solve two rather significant problems facing businesses today:

• Chronic employee burnout

• Not effectively supporting employee's emotional and psychological needs

Crowley's framework addresses employee well-being in terms of ensuring that people feel valued, respected, deeply connected to their colleagues, and empowered in their roles, not in terms of personal health practices such as diet, exercise, or spirituality. Corporate managers: Putting a foosball table in a break room does not increase well-being or engagement. Being meaningful in a leader as coach role is a great way to start. What did the Covid experience working from home teach us? A worthy guess is that many professionals realized they could fulfill emotional and psychological needs more readily at home while remaining productive with their daily work.

Recent trends suggest this. Francis shares:

Yet Americans still work from home about a quarter of the time—much like in 2023, said Nicholas Bloom, a Stanford economist who has helped run a monthly survey of 10,000 Americans on the topic since 2020. Return-to-office ultimatums at big companies get the most attention, but most smaller companies continue to allow at least some remote work as a matter of routine, Work Forward’s data show.

Well-Being is key today and effective

Leaders Understand Well-Being.

The Power of Employee Well-Being | Book Review

“Most stressed that investors never held CEOs accountable for

engagement because other well-established metrics for evaluating

organizational performance were deemed more important." (p. 2)

Mark Crowley's timely work is a worthy companion to 2021's Wellbeing at Work by Jim Clifton & Jim Harter. This is no surprise, as Crowley has tracked classical engagement metrics (think Gallup's trademarked Q12) as well as any contemporary author. We should consider Crowley's twelve concise chapter takeaways as updated metrics for any professional concerned about organizational performance.

An intentional pivot toward elevating well-being will help solve two rather significant problems facing businesses today (p. 3):

• Chronic employee burnout

• Not effectively supporting employee's emotional and psychological needs

DeNeve's (Oxford professor Jan-Emmanuel De Neve) most unexpected and profound conclusion is that the greatest driver of employee well-being is belonging (p. 5). Crowley's framework addresses employee well-being in terms of ensuring that people feel valued, respected, deeply connected to their colleagues, and empowered in their roles, not in terms of personal health practices such as diet, exercise, or spirituality (p. 8). This review reflects on Crowley's twelve key findings offering supporting evidence his roadmap is vital today.

12 Well-Being Findings

1. Know Thyself

This finding mirrors an Academy Leadership Excellence Course (LEC) day one, where focus is on learning about self. Most leaders don't believe they need to do this work at all. Research shows that 95 percent of people believe they are self-aware, while just 10-15 percent (at best) truly are (p. 18).

2. Drop a Pin

What actually proves to differentiate superstar performers, Potterat said, is a mastery of four learned behaviors (pp. 24-25):

• Are highly resilient.

• Commit to making incremental improvements.

• Keep their minds focused on the only three things they can directly control: their attitude, their effort, and their actions.

• Have highly refined value systems and have developed a personal "credo."

We may think of Potterat's findings as a combination of deliberate practice, as defined by Anders Ericsson in Peak along with living one's Personal Leadership Philosophy, or PLP.

3. Emotions Power the Workplace

The rather important leadership takeaway here is that how managers make us feel, and not what they make us think, drives employee commitment, loyalty, productivity, and well-being (p. 30). This is a timeless lesson with roots in classical rhetoric. In a highly technical workplace, it's easy to focus on logos, or the logical argument for your point, rather than pathos, or the ability to connect with others emotionally.

4. Embrace our Shared Humanity

It's always been my experience that when employees are made to feel that they are valued as human beings, they will instinctively reciprocate by taking steps to minimize, as much as possible, any impact the personal challenges they are facing might have on the responsibilities they have at work (p. 37).

In Culture Shock, Team Gallup recommends becoming a leader as coach by having one meaningful conversation per week with each employee. This allows us to connect at an instinctive and motivational level.

5. Curate Connection and Belonging

According to Professor Geoffrey Cohen, belonging is the feeling that we're part of a larger group that values, respects, and cares for us -- and to which we feel we have something to contribute (p. 43). Identify behaviors that align with your team's values and mission and create unique rituals around those behaviors (p. 45). Put more simply, we should align our PLP with our organization, then live our leadership philosophy daily.

6. Be a Positive Force

The single most important factor that differentiated high-performing teams from low-performing teams was the ratio of positive to negative interactions employees experienced -- between one another, and between themselves and their managers (p. 48).

In Thanks For The Feedback, the authors articulate three forms of feedback:

• Appreciation

• Evaluation

• Coaching

Establishing a high-performing team may be started by greatly reducing the amount of evaluation and increasing the amount of [performance] coaching.

7. Turn Over Every Stone

We're wise to proactively align ourselves to the speed of change by embracing lifelong learning, seeking new information, exploring different perspectives, and questioning the status quo (p. 53). Curious-minded leaders know that they and their people can never stop learning -- and, more importantly, they never should (p. 58).

In From Strength to Strength, Arthur Brooks reminds us that we may continue gaining fluid knowledge, despite our age, while sharing crystalized knowledge gained over a lifetime (think Leader as Coach).

8. Step Into the Fog

Rick Wartzman and Kelly Tang (Bendable Labs): Being comfortable with haziness and reacting with nimbleness ... are the most prominent hallmarks of being an effective leader in our turbulent times (p. 61). Recall in Navy Seal Jeff Boss' Navigating Chaos, subtitled How to Find Certainty in Uncertain Situations, the key trait for navigating such situations is curiosity.

9. Loosen Your Grip

It's a fatal flaw for managers to believe that employees won't work hard or be effective unless their closely monitored or even micromanaged (p. 67). Autonomy, mastery & purpose are the key to motivation in the workplace today. According to Dan Pink (Drive), these are the top three motivators once people believe they are paid enough at work.

10. We Instead of Me

Collaboration, mutual trust, and cooperation are crucial to developing new technologies and to achieving virtually every important organizational goal (p. 73). All great coaches in collegiate and professional sports knowingly create cultures of initiative and achievement, with a special emphasis on collaboration (p. 74). Adapting a performance coaching mindset is a great way to start. In Coaching to Develop People workshops, we define performance coaching as the process of equipping people with the tools, knowledge and opportunities they need to develop themselves and become more successful.

11.Growth Creates Happiness

To be an enlightened leader today is to understand that the limits of human potential are mostly imagined (p. 79). I've strongly believed that workplace leaders should not only self-identify as being more of a coach than a manager, they should dedicate more of their time to coaching than managing (p. 82). The easiest way to begin coaching rather than managing or evaluating is to spend more time asking active questions followed by supportive actions, rather than telling others what to do followed by impersonal evaluation.

12. Care About - Even Love - Your People

Dachner Keltner UC Berkeley social scientist informs us:

We no longer earn power by being self-focused, but by consistently

acting in ways that improve the lives of others. Power is expressed

in advocacy, compassion, respect, attentiveness to human feelings,

and gratitude toward others (p. 86).

Crowley's Lead From the Heart essentially concluded the same.

Summary

Crowley's findings from his Oxford meeting with Jan-Emmanuel De Neve provide final validation (pp. 91-93):

• Employee well-being is mostly on us (as leaders), not them.

• Unlike with engagement, a focus on employee well-being is a true win-win

• Measuring well-being should have little complexity.

• "And, at any given time, we generally want to know two things: how people feel at work, and what may explain those feelings."

How people feel at work and how they feel about their work --

determine employee well-being. (p. 5)

Team Crowley generously provided a copy of the book for review.

Coaching Story | From Manager to Leader

This year, common Leadership Excellence Course (LEC) shared expectations and follow on Executive Coaching session topics include:

• Becoming more strategic

• Gaining confidence as a leader

• Overcoming imposter syndrome

• Becoming a leader

This was particularly evident during a Leadership Development Program (LDP) consisting of administrators of a long term construction company client. At the end of the LDP, it was clear that about half the attendees view themselves more as leaders now, while the other half may take a bit more time.

A key part of this journey is developing our Personal Leadership Philosophy. Recall, in our Leader’s Compass workshops, establishing your Leader’s Compass does not mean that you are expected to become a philosopher, but it does mean determining…

• Who you are

• What you value

• What your priorities are

• What you will stand for

• What you will not stand for

and making sure that everyone knows and understands this.

Take a look at this email from last week:

“Hope you’re doing well! I wanted to let you know I’ve taken a new position at a [new] company, starting next week. I’ll be a data analytics manager, helping them build out a new analytics and AI practice with commercial clients. I’m pretty excited to potentially scale something new, and it comes with a very large pay raise, more than I would have made in the next several years at [current company].

I’m copying my personal email here so we can stay in touch. I also wanted to say thank you – your advice helped me position myself in a way that led to this opportunity. They said they’re looking for someone to lead a team and connect the dots between the tech and business aspects of their projects, which is exactly how I’ve been branding myself over the last year. I also shared my leadership philosophy doc with them in the interview process. It seemed like a bit of a risk, but I figured if they didn’t like it, then it wouldn’t be a good fit anyway.”

Isn’t that great? The client lived his leadership philosophy, and concurrently positioned himself as a technical leader, which is sorely needed in many organizations today. And, by the way, his increase in pay validates how much leadership skills are in demand. A timely example of growing

From Manager to Leader.

Influence & Insight | September 2025

Leadership Story | Leaders Make it Safe

At a recent client leadership retreat we explored Crucial Conversations. Recall the nine dialog skills comprising most of the book:

1. Choose Your Topic

2. Start with Heart

3. Master My Stories

4. Learn to Look

5. Make it Safe

6. State My Path

7. Explore Other Paths

8. Retake Your Pen

9. Move to Action

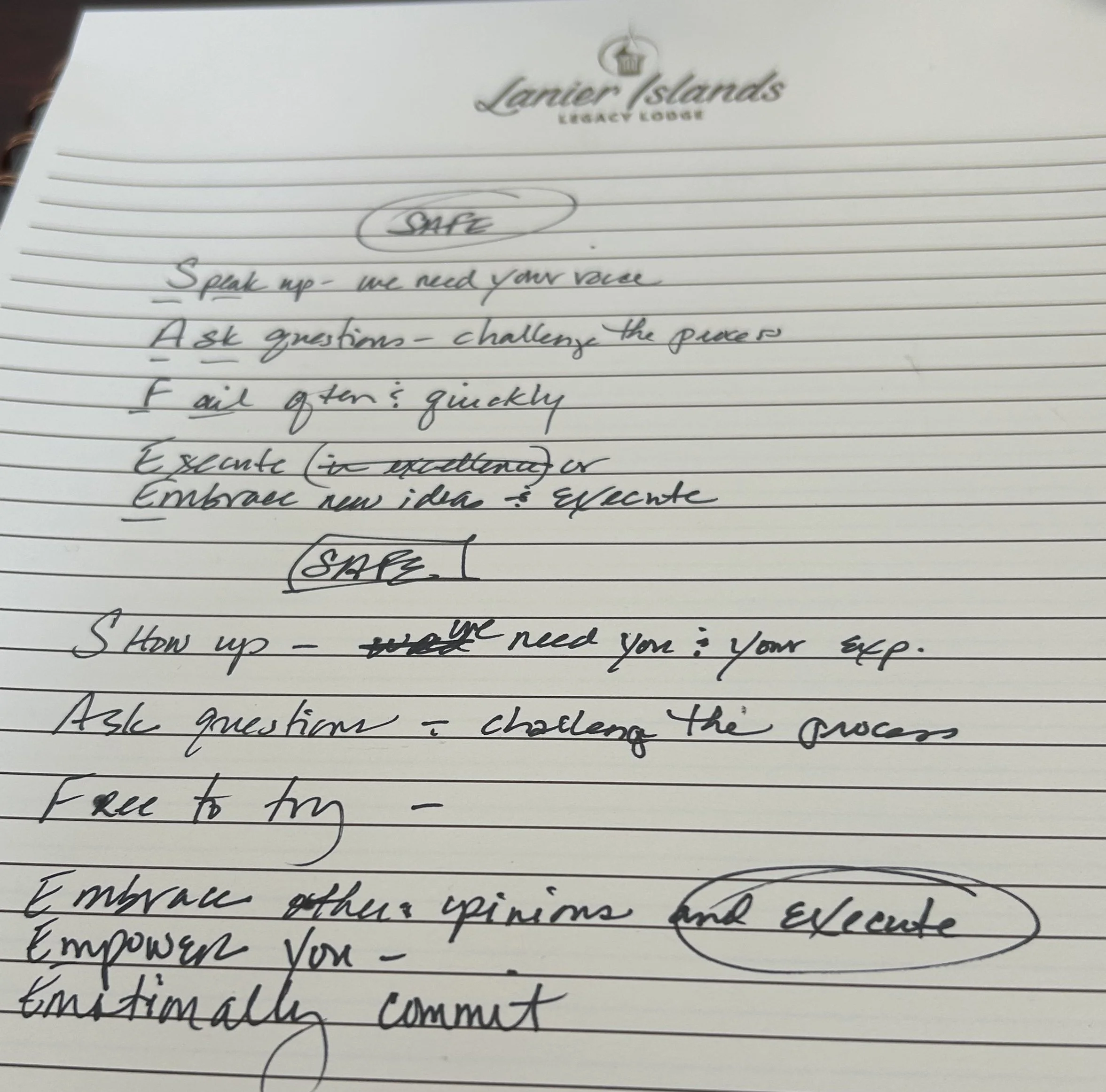

We really got into number five, Make it Safe. One of the team participants came up with the idea of turning SAFE into an actionable acronym.

Here’s what it first looked like:

Notice the lower part where the letter E is elaborated upon. Turns out this attendee is familiar with Kouzes & Posner’s five Leadership Commitments:

• Model the Way

• Inspire a Shared Vision

• Challenge the Process

• Enable Others to Act

• Encourage the Heart

The natural next step was to connect SAFE with the five commitments, yielding:

How about that? Now our client has a unique way to open up, encourage dialogue, and grow the organization.

Leaders Make it Safe.

Grit | Book Review

“It was this combination of passion and perseverance that made

high achievers special. In a word, they had grit" (p. 8).

Angela Duckworth's well-researched classic serves as a lifetime reminder we should appreciate what others have accomplished rather than passively claim others simply are just "born that way," or are "naturals." This "naturalness bias" is a hidden prejudice against those who've achieved what they have because they have worked for it, and a hidden preference for those whom we think arrived at their place in life because they're naturally talented (p. 25).

Consider the significance. Mythologizing natural talent lets us all off the hook (p. 39). If we believe another person's performance comes easily, we've granted ourselves an excuse for lesser performance, or worse, for not trying.

This review explores Duckworth's distinction between internal grit, which we may apply for self-improvement; and external grit, which we may apply in our leader as coach role.

I grew less and less convinced that talent was destiny and more and more intrigued by the returns generated by effort (p. 20).

Internal Grit

Deliberate practice is for preparation,

and flow is for performance (p. 132).

Chapter seven is marvelous. Duckworth shares her insights gained from meeting and working with Anders Ericsson, who defines deliberate practice (see Peak) as consisting of (p. 137):

• A clearly defined stretch goal

• Full concentration and effort

• Immediate and informative feedback

• Repetition with reflection and refinement

The idea that if we spend 10,000 hours on an activity, we'll become world class has unfortunately become popular. Ericsson's findings were specifically that 10,000 hours of deliberate practice leads to world class performance, not natural talent.

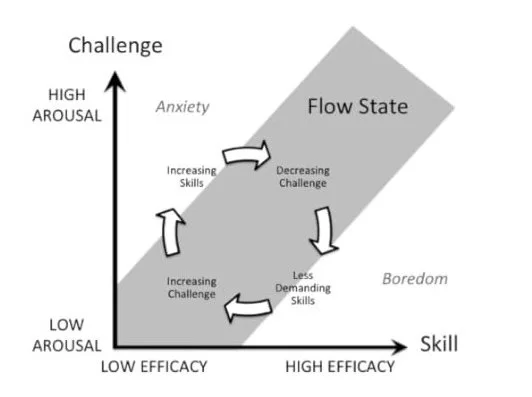

Interestingly, Duckworth encountered Mihaly (Mike) Csikzentmihalyi (see Flow) shortly after working with Ericsson. For Csikzentmihalyi, the signature experience of experts is flow, which is best expressed visually as:

After studying the two concepts, Duckworth came to understand that flow and grit go hand in hand (p. 131). When we watch Steph Curry repeatedly sink 3-point shots, we're watching him in a state of flow, without thinking about his thousands of hours of deliberate practice which made his performance possible. Duckworth now believes that the primary motivation for doing effortful deliberate practice is to improve your skill (p. 131).

How best to cultivate our grit? Duckworth recommends that a growth mindset leads to optimistic ways of explaining adversity, and that, in turn, leads to perseverance and seeking out new challenges that will ultimately make you even stronger (p. 192).

External Grit

Duckworth continuously seeks indicators, or predictors of grit, and found that follow-through in high school extracurriculars predicted graduating from college with academic honors better than any other variable (p. 229). Perhaps we should consider follow-through or demonstrated determinism in adjacent skills or hobbies when hiring or building teams. What we have tended to find is that all that energy, drive, and commitment -- all that grit -- that was developed through athletics can almost always be transferred to something else (p. 235).

Similarly, phrases such as relentless pursuit, dogged determinism, or continuous improvement in our Personal Leadership Philosophy may foster an environment where grit is both welcomed and nurtured.

Another idea: Incorporate deliberate practice into After Action Reviews (AARs). AARs already focus on feedback and refinement. We can simply modify the commitment to improve into a stretch goal with singular focused intensity. Imagine instilling this habit into your organization creating a chain of performance breakthroughs.

Summary

Passion and perseverance. That's the recipe. Hat tip to Duckworth for mentioning both Tom Deierlein and Robert Caslen in Chapter 12, A Culture of Grit.

What excites me most is the idea that, in the long run,

culture has the power to shape our identity (p. 247).

Coaching Story | Leaders Create Motivational Environments

Zoom coaching sessions sometimes reveal extraordinary progress. A most conscientious client shared with me progress with the single person she currently serves as a Career Manager (CM) for. Turns out within her company, internal motivational assessments are available (pretty cool). My client told me one of the original motivators for her protégé two years ago was money. That’s entirely understandable for a a recent college graduate trying to figure out how to make ends meet.

Interestingly, my client surveyed her protégé’s motivations again. This time, however, money dropped in the rankings, and the factors that increased were:

• Flexibility

• Personal growth

• Recognition

• Stability

Recall that according to Dan Pink (see Drive), once people feel they are paid enough to not worry about their salary, autonomy, mastery and purpose become the primary motivators.

This coaching session appears to validate Pink’s findings. Flexibility is our protégé’s expression of autonomy, personal growth is our protégé’s expression of mastery and perhaps recognition is our protégé’s expression of purpose. Interestingly, note the addition of stability, likely a result of uncertainty created by both Covid and turbulence in any organization largely dependent of defense work.

I asked my client if she wished to serve as Career Manager for more than one. She enthusiastically said yes. My impression is this client is on a genuine leader growth path.

Leaders Create Motivational Environments.

Influence & Insight | August 2025

Leadership Story | Leaders Inspire

For most professionals, drafting and revising a Personal Leadership Philosophy can be a daunting, if not anxiety-driven event. This past month the twelfth Leadership Development Program cohort from a long-term client graduated in Texas. This client provides vital infrastructure to our country via, high voltage electrical transmission lines (T-Lines), electrical substations and a rapidly emerging Engineer, Procure & Construct (EP&C) services business.

Usually one of the company’s senior leaders is available at program kickoff, offering support and maybe an inspiring story. Not this time. Everyone is just a bit busier this year.

What to do?

Rather than attempt articulating what one of the executives might say, I read the company president’s Personal Leadership Philosophy aloud launching the course. The opening paragraph of this leadership philosophy is a statement of humility, loyalty and deep commitment.

What I wasn’t ready for was the effect of this leadership philosophy on the eight attendees, most from humble or hardscrabble backgrounds, and many from other countries. It’s as though after hearing their company president reveal who he really is, where he comes from, and his deep commitment to every individual in the company, the course attendees realized it was ok to share who they really are too.

This was not your typical blue collar construction company leadership course.

This was a demonstration that the best leaders genuinely inspire.

Unlocking Creativity | Book Review

“When surveyed, CEOs across a variety of industries

have identified creativity as one of the most

desired leadership qualities for the future." (p. xi)

Subtitled How to Solve any Problem and Make the Best Decisions by Shifting Creative Mindsets, by Bryant University’s Michael Roberto, takes aim at many common and chronic mindsets, frequently found in larger organizations.

Interestingly, Roberto found that while executives named innovation as a top priority, most employees felt that they were not encouraged to develop new ideas, and they did not have the time and resources required to do so (p. 10). This tendency seems strikingly familiar to the Knowing-Doing-Gap described in detail by Pfeffer and Sutton.

Roberto details six creativity-inhibiting mindsets (p. 17):

1. The Linear Mindset

2. The Benchmarking Mindset

3. The Prediction Mindset

4. The Structural Mindset

5. The Focus Mindset

6. The Naysayer Mindset

Which may be considered detailed Action Plans that naturally follow Pfeffer and Suttons' Eight Guidelines for Action:

1. Why before How: Philosophy Is Important.

2. Knowing Comes from Doing and Teaching Others How.

3. Action Counts More Than Elegant Plans and Concepts.

4. There is No Doing Without Mistakes. What is the Company’s Response?

5. Fear Fosters Knowing-Doing Gaps, So Drive Out Fear.

6. Beware of False Analogies: Fight the Competition, Not Each Other.

7. Measure What Matters and What Can Help Turn Knowledge Into Action.

8. What Leaders Do, How They Spend Their Time and How They Allocate Resources, Matters.

This review highlights selected portions of Roberto's six mindsets and suggests that by overcoming them a team or organization both increases creativity and crosses the Knowing-Doing-Gap.

Resistance

Roberto mentions how frequently organizational cultures do not promote experimentation and risk-taking behavior (p. 9). We could say many corporate leaders don't "walk the talk." Management rules the day. Rewards and incentive systems focus on efficiency and productivity, and they discourage learning and exploration (p. 9).

Fear is the likely culprit. The bias of fear impedes our ability to be creative (p. 12). Pfeffer and Sutton concluded the same with fear fostering Knowing-Doing gaps, so we must drive out fear.

Mindsets

The Linear Mindset

Many organizations fail to understand and embrace the iterative and discontinuous nature of the creative process. They mistakenly try to move from analysis to idea formation to execution in a step-by-step manner (p. 17). Roberto diagrams a couple typical processes on page 25. Creativity and genius don't follow systemic patterns. For example, Leonardo (Da Vinci) embraced a learning by doing approach in all creative endeavors (p. 24). Consider the iterative test/failure/improve methodology employed by SpaceX today.

Most executives prefer to hire specialists with deep yet narrow expertise, rather than curious polymaths. They desire control, certainty, and order (p. 26). Yet, action counts more than elegant plans and concepts. Likewise, Pfeffer and Sutton found the best way to cross the Knowing-Doing-Gap is to learn by doing.

Many companies have failed to make the shift from the traditional planning mindset to a learning-by-doing approach (p. 35). By acting first, we may better learn afterward to measure what matters and what can help turn knowledge into action.

The Benchmarking Mindset

Firms study their competitors closely, but in doing so, they experience fixation. Consequently, they adopt copycat approaches rather than distinctive strategies (p. 17). Business economist Robert Kennedy discovered that distinctive, original shows consistently outperformed trend followers (p. 46). Pfeffer and Sutton found that benchmarking is usually superficial, never asking why successful organizations do what they do, or what underlying philosophy drives decisions.

Rather than simply benchmarking direct rivals, companies need to think broadly about the full range of substitutes against which they compete (p. 60). This broader definition is the competition to fight against.

The Prediction Mindset

Managers have a desperate desire to see what's next, and they exhibit overconfidence in the ability of experts to forecast the future. The insatiable need to predict just how big ideas will become actually impedes creativity (p. 17).

Tetlock discovered that how people think matters

more than what they already know (p. 72).

When executives demand to know whether an innovation will move the needle, they presume that innovators can distinguish blockbuster hits from niche products at the early stages of the product development process (p. 79).

How an organization responds to mistakes will define, in large part, it's culture.

The Structural Mindset

Managers often resort to changes in organizational structure as a means of stimulating creativity and improving performance. They fail to recognize the limited efficacy of redrawing the lines and arrows on the organization chart time and again (p. 17).

Pfeffer and Sutton recommend observing what leaders do, and how they spend their time and how they allocate resources, matters. Roberto cites Zappos' -- who empower employees to do whatever it takes to please the customer (p. 87).

What [Google's] research showed us was that it's less about who is on the team and more about how people interact that really makes a difference (p. 97). This is what we find in our Creating a Motivational Environment workshops. The setting we create matters. In the creative process, psychological safety enables team members to propose unconventional solutions (p. 99).

The Focus Mindset

Organizations believe that teams will excel at creative work if they focus intensively, perhaps even secluded from their colleagues. They fail to recognize that the best creative thinkers oscillate between states of focus and unfocus (p. 17). Roberto cites inventor Nikolas Tesla who explained "Originality thrives in seclusion free of outside influences beating upon us to cripple the creative mind" (p. 115). Once free of influence or processes, a natural rhythm may form. The best creative thinkers toggle between focus and unfocus throughout their lives, much like Twain, Tolkien and Wordsworth (p. 131). This process of action and relaxation counts much more than elegant plans & concepts.

The Naysayer Mindset

Managers encourage people to critique each other's ideas early and often. Unfortunately, the failure to manage dissent and contrarian perspectives causes many good ideas to wither on the vine. Evaluation is the dominant form of feedback. Unfortunately, in many organizations today, the critics and naysayers outnumber the idea generators and the doers by a wide margin (p. 142).

Consider a coaching approach driven by a desire for everyone to learn. Ask questions.

The best devil's advocates practice the Socratic method,

rather than delivering a lecture. (p. 151)

Summary

Be the curious leader as coach.

As a leader, consider yourself a teacher at heart --

not the sage on the stage imparting wisdom from on high --

not that kind of teacher (p. 161).

Michael Roberto generously provided a copy of the book for review.

Coaching Story | Leaders Have a Toolbox

What do most of us do with course materials after a professional training program? Maybe display a diploma on our wall and tuck our course binder and books together on a bookshelf?

A very conscientious client reached out to me after our our recent Graduate Leadership Course. Recently promoted, she really wanted to share key takeaways with her supervisor team after identifying:

Key Skill Themes:

Leading by example

Adaptability

Clear communication

Empathy

Team morale

Job-specific skills

Active listening

Vital Skills Often Forgotten:

Encouraging team members

Promoting work-life balance

Developing leadership skills

Skills to Improve:

Coaching techniques

Attention to detail

Self-advocacy

Motivating staff

Problem-solving abilities

Time management

Staff retention strategies

Challenges Highlighted:

High turnover rates

Managing and training inexperienced (“green”) staff

What a terrific outline. I wasn’t sure how aware my client was that most of the items on her list were addressed in either our original Leadership Excellence Course or the follow on Graduate Leadership Course. So we scheduled a half day on site and simply reviewed key teachable points of view from both courses, allowing my client to highlight growth areas for her new supervisors. Many drawings on flip charts. The supervisors left the session more motivated, and the time together reminded both of us that two leadership courses provide a wide range of useful tools.

Leaders have a toolbox.

Influence & Insight | July 2025

Leadership Story | Leaders Inspire Others

At the beginning of our Coaching to Develop People workshop, the final workshop in a three-day Leadership Excellence Course, participants share stories of inspiring coaching figures often recalling decades old thoughts and emotions. It’s a reminder that a in a leader as coach role we unknowingly may deeply affect each other.

Such a reminder occurred this past month at a long term client site when a March 2016 program attendee approached me during routine setup up for a two day event. Nine years ago, my Canadian colleague was part of a ten-person cohort of a customized once a year emerging leaders program. As we met I offered congratulations on my prior graduate’s successful Master’s Degree completion recently posted on LinkedIn.

We each grabbed a chair, as my friend wanted to tell me about the past nine years. March 2016 was a turning point for him, the beginning of an intellectual awakening, and the Master’s degree was just part of it. His new title is Director of Training, at the corporate level, and my colleague invited me to his office where he eagerly showed me two documents.

First was the instructor script for a Construction Manager & Superintendent Training plan. Highlights of the document included Command Presence – The Field Must Feel Your Leadership. Key phrases included Visibility creates accountability and confidence, You don’t lead from the truck, you lead from the structure pad, from the staging yard. In short, your presence sets the bar for crew professionalism. This was terrific, it looked like a Personal Leadership Philosophy in action.

Second was a Processes Plan for Powerline Project Support Team document. Highlights of this included Cross-Training Initiatives, in particular Knowledge Sharing Forums. This will be done via informal evening sessions where experienced team members share lessons learned. This plan reminded me of After Action Review findings or knowledge sharing described by Stanley McChrystal in Team of Teams.

For nine years my friend has been on an amazing, positive journey. I invited him to attend a Graduate Leadership Course and will send him a signed copy of Team of Teams if he doesn’t have one already.

We never know when we may inspire others.

Wellbeing at Work | Book Review

“The five key elements of wellbeing are career, social, financial,

physical, and community - in that order." (p. 7)

Subtitled How to Build Resilient and Thriving Teams, is the second of Jim Clifton & Jim Harter's three book series published between 2019 and 2023 and extends beyond Gallup's focus on engagement to include concepts of Wellbeing and Net Thriving.

Published during Covid-19, the authors found that the five elements of your life that affect your wellbeing are interdependent (p. 16). This is reminiscent of Lisette Sutherland's Work together Anywhere, which persuasively demonstrated the emergence of hybrid work environments long before the pandemic.

Clifton and Harter offer three additional human condition categories: We determined the thriving, struggling and suffering categories based on analytics from over a million respondents across 160 countries. (p. 23)

• Thriving: These respondents have positive views of their present life situation and have positive views of the next five years.

• Struggling: These respondents struggle in their present life situation and have uncertain or negative views about their future.

• Suffering: These respondents report that their lives are miserable and have negative views of the next four years.

This review focuses on Workplace Wellbeing opportunities and risks to a Net Thriving Culture.

Workplace Opportunities

Managers don't seem to be very effective creating wellbeing at work:

Spending time with their manager is the worst part of the day for

employees, according to an approach called National Time

Accounting that asks people detailed questions about their

time use throughout the day. (p. 41)

The authors suggest using proven methods to transition your managers' mentality from boss to coach. Think of the instinctive needs dimension of an Energize2Lead Profile, whose colors represent:

• Motivational Needs

• Learning Style

• Survival Instincts

• What we LISTEN FOR

A boss likely focuses on the task or project at hand, while the leader as coach focuses on the more significant aspects of wellbeing. Recall from Culture Shock that holding one meaningful conversation per week with each employee is the best way to increase engagement. Since career is the most significant wellbeing element, effective coaches should focus on creating an environment where thriving in what you do every day makes for stronger relationships (p. 35).

During Academy Leadership Creating a Motivational Environment workshops, we ask "Do Leaders Motivate People?" Rather than believe a boss or coach can make someone do something, we should focus on whether or not we're creating a thriving environment. An engaged employee wakes up in the morning thinking about the work they are going to do that day -- and that work is interesting and challenging to them (p. 42).

Wellbeing is also a financial opportunity: If organizations doubled the percentage of their employees who have a best friend at work, they would realize fewer safety incidents, higher customer ratings and as much as 10% higher profit margins (p. 45).

How to start? Ask employees who they enjoy working with, who has common goals, and who they would like to partner with on future projects (p. 52). An easy place to address this when composing our Personal Leadership Philosophy, is perhaps in the Operating Principles section. Another place is where we articulate our Priorities. For example, make communicating the importance of physical wellbeing an expectation for managers (p. 69). Finally, we may stress the importance of team identity, a powerful motivator. People get a great sense of fulfillment when they feel they are part of something bigger than themselves. Communities can give people that feeling (p. 71).

Risks

The authors define a net thriving culture as one that improves people's lives and performance - beyond typical wellness programs. The four biggest risks in designing and activating a net thriving culture are (p. 87):

• employee mental health

• lack of clarity and purpose

• overreliance on policies, programs and perks

• poorly skilled managers

Our leadership philosophy addresses clarity and purpose. Let's take a closer look at policies, programs and perks. Particularly in larger organizations, we'll frequently notice a plethora of administrative detritus nobly attempting to replace the actions and energy of a leader as coach. In Germany and in the U.S., Gallup found that people with a bad manager had even worse wellbeing than those without jobs (p. 91).

Support for developing managers into leaders must come from the top. Managers are often stuck between organizational decisions and front-line implementation. When managers are taught coaching skills -- which include collaborative goal setting, ongoing feedback and accountability -- they will develop high levels of trust with their employees (p. 101).

Employees usually don't leave companies; they leave lousy supervisors. Of the four risks, poorly skilled managers are the greatest risk. Managers are the single most important factor in the engagement and performance of your workforce (p. 109).

Summary

The best organizations can exceed 70% engaged employees, and the following common themes emerge (p. 124):

1. Culture change was initiated by the CEO and board.

2. They transformed managers from boss to coach.

3. They practiced highly effective companywide communication.

4. They held managers accountable for engagement and performance.

When comparing top -- and bottom-quartile business units and teams, all of this accumulates into a 23% profitability advantage (p. 125).

An interesting observation:

While employee engagement has been on the rise for the past 10 years, as of this writing, 36% of U.S. workers and just 22% globally are engaged (p. 19). It may well be that increased autonomy from the emerging hybrid work environment has increased engagement. Let's see if post Covid return to office policies negatively affect the generally positive trend in employee engagement.

Never forget that you are here to serve. Serve the organization first,

then your team, and long afterward yourself. (p. 223)

Team Gallup generously provided a copy of the book for review.

Coaching Story | Manager to Leader

Many Leadership Excellence Course (LEC) registrants are very smart, and highly trained subject matter experts (SMEs) in one or more fields. One such LEC attendee’s listed Leadership areas you want to improve included communication, efficiency and team time management. Notice the focus on management and efficiency. This wasn’t surprising, since this professional has degrees in computer Software Engineering and Computer Science, and is a key contributor to one of the biggest telecommunication networks in the world.

Interestingly, during individual participant introductions, this engineer mentioned wishing to learn more about leadership, not just management. Wonderful. Over the course of three days, LEC participants realize the differences between managing and leading, and ultimately create an action plan listing three leadership behaviors which inform our follow on coaching sessions.

We just completed our first coaching session addressing the following leadership behaviors:

Behavior 1: Micro-managing

What it looks like when I'm successful: I have assessed the capabilities of the people I lead and I have allowed them to work their tasks without me constantly checking over their shoulder. They know that I am nearby to assist.

Behavior 2: Delegating

What it looks like when I'm successful: I have delegated tasks not because of lack of bandwidth but to challenge and allow for the the people I lead to grow.

Behavior 3: Open to other approaches.

What it looks like when I'm successful: I have allowed the people I lead to share how they believe we should go about something. I will save my approach until the end and ask for their opinion.

One of the key takeaways from the coaching session was my colleague’s realization that he can’t “train the work ethic,” or put another way, make someone do something. He shared that he needs to find out what motivates others.

It’s hard to recall a more rapid transition from a SME or management perspective to a leader point of view. Now in a leader role, this graduate is far more interested in finding our what motivates others, and looking for intrinsically motivated candidates to join the team rather than selecting employees who wish or need to be managed. Should be a wonderful second coaching session scheduled more mid-July.

From SME to Leader.

Influence & Insight | June 2025

Leadership Story | Leaders Make it Safe

Frequently when facilitating a leadership course, one or more attendees mention that direct reports appear reluctant to provide feedback. This pattern is usually most noticeable during open enrollment self-evaluations at the beginning of feedback, motivation, conflict & accountability workshops. Typically a low participant score during the initial feedback workshop is a good predictor low feedback-related scores will follow during the other three workshops. Another indicator is during in-house programs when discussion groups collectively pull back expressing reluctance to openly identify and discuss visible issues within the organization, perhaps out of fear they may be observed by their bosses within the company.

In both cases attendees are signaling their environment is not safe for open discussion.

What do we mean by safe?

The popular book Crucial Conversations offers an excellent definition of safety, listed as the fifth of nine dialogue skills.

According to the authors, Make It Safe means:

• Stop the action when the conversation becomes unsafe

• Talk about most anything (without silence or violence) to keep people sharing

• Decide which Condition of Safety is at risk

• Mutual Purpose

• Mutual Respect

• Apologize when appropriate

• Contrast to fix misunderstanding

• Work back to Mutual Purpose and Mutual Respect

On the first day of a recent, large in-house program, several discussion groups seemed uncomfortable openly expressing concerns about their sustained high-intensity workload. By the second day, the audience appeared much more relaxed in the same small groups. From a facilitator standpoint, it seemed that the condition of Mutual Purpose was achieved, perhaps a recognition by the workshop attendees that the overall organization recognizes common challenges while rapidly growing.

An easy way to think about the book Crucial Conversations, or challenging conversations in general, is that we cannot start a difficult conversation without Mutual Purpose and we cannot sustain it without Mutual Respect.

Leaders Make it Safe.

How To Do The Inner Work | Book Review

“I had been working way too much and my habits

and thinking patterns caused me to feel intense pressure

on a daily basis. I wanted to be the perfect manager

who didn't let anyone else down - no matter what." (p. 1)

Susanne Madsen's deeply personal and introspective work may be mistakenly labeled a self-help work but rather focuses on commonly neglected leadership behaviors vital to our influence and effectiveness. Let's briefly examine two forms of leader conduct, energy management and decision-making.

Madsen reminds us that when our basic need for love, acceptance, and safety isn't met in certain situations, our survival instinct kicks in (p. 13). During an Academy Leadership Energize2Lead (E2L) workshop, the significance of our instinctive needs quickly surfaces, and this dimensional profile is summarized as:

• Motivational needs

• Learning style

• Survival instincts

• What we LISTEN FOR

Like a drowning victim, survival becomes an overwhelming priority, leaving no energy for listening, learning, or for anyone else. We must take care of ourselves first, even though it's easy to get fooled into thinking that the answer to our problems lie outside of us (p. 5).

Jim Collins' hierarchy diagram from BE 2.0 serves as an eternal guide regarding a leader's decision-making process. Vision, strategy, and tactics can change over time; enduring organizations adapt to evolve and survive. What does not change, however, are our core values and beliefs.

This review primarily focuses on Madsen's Chapter 2: Restoring Your Energy Levels & Chapter 3: Living By Your Core Values.

Energy

Madsen observes if you consistently use more energy than you generate, your tank will begin to run empty, and you will feel tired and unhappy (p. 24).

Tony Schwarz's energy diagram from The Power of Full Engagement is helpful. Madsen is likely describing negative uses of energy, frequently encountered in environments where we feel pressure to be "on" 24/7. Look at the lower left quadrant of the energy diagram. These feelings and behaviors occur when we remain in our E2L instinctive dimension. If there is too much stress and obligation in your life, you'll stay stuck in survival mode. That will cost you a lot of energy and can have a detrimental effect on your physical, mental, and emotional health in the long-term (p. 25).

Madsen's findings mirror Schwartz's: It may feel counterintuitive to slow down and take time out for yourself where there is so much you want to do, but if you keep running, your will make matters worse, and you won't be able to free up mental space for a new level of thinking to energy (p. 27). We should toggle between the right two quadrants, counter to false pressure to be professionally busy. One of the beliefs I picked up in my childhood is that being busy and productive is always good, and rest and relaxation is lazy (p. 33).

Values

Look at the small intersection in the Passion Circle illustrated on page 65.

Effective leaders frequently take time to reflect, or discover where passion, curiosity and professional skill intersect. We're more likely to discover this area when we're in a positive and relaxed state, perhaps capturing our thoughts in a journal. Madsen suggests we iterate with the passion circle exercise until finding the intersection that allows us to best express our values and live our purpose (p. 69).

This may sound similar to developing a Personal Leadership Philosophy (PLP). As we continue growing as leaders, we'll increasingly make decisions based on our PLP, or our core values, regardless of other circumstances. While you might think you need to make a huge, expensive lifestyle change to feel different, often it's the small things in life that have the biggest difference on our wellbeing (p. 45).

Additional Nuggets

Madsen's personal experiences describe how she has mastered occupying a positive, yet lower energy state of mind. Breathwork is one of the most powerful, quick, and accessible ways to help you center yourself whenever you feel tense, emotional, or stressed (p. 81).

Madsen also reminds us that we're in control of our decision making process, or how we react to events. With mindful awareness, we can take a step back, observe ourselves, dialogue with the emotion, and choose a different response (p. 146). This reminds us of the [relatively new] Retake Your Pen dialogue skill found in the 3rd edition of Crucial Conversations. We can choose our response after landing in our instinctive E2L dimension.

Summary

We can't lead or influence others without first understanding self:

But instead of clinging to external events and physical things,

let that something be your own inner resources

and the strength of your spirit. (p. 155)

Thank you Tom Corson-Knowles for providing a copy of Susanne’s book for review.

Coaching Story | Leaders Make Personal Connections

During a second coaching session this past month, a client shared a powerful story. She works primarily in the greater Denver area, but most of her team works in Virginia. In our first coaching session following our early April leadership course, my colleague expressed a genuine enthusiasm to better connect with her team. Maybe our feedback workshop triggered this, as we discuss how leaders really have two essential leadership tools:

Our Actions

Our Words

Given my client’s geographic isolation, she likely realized her actions were underrepresented and wanted to do something about it. Spending her own money on travel, she made her way to Virginia, ready with new tools from our nine-workshop Leadership Excellence Course. During the trip, she conducted one-on-one “tag ups” with each member of the team, sharing highlights from her Personal Leadership Philosophy, and revealing findings from her own motivation assessment.

Sharing her individual motivation assessment first, or what types of activities she finds energizing and what types of activities are energy drainers, allowed this emerging leader to later ask everyone on the team questions such as what are your normal work hours and daily rhythms? My client learned a lot about each of her colleagues and likewise improved project planning as well as goal execution. Recall from our Energize2Lead workshop, understanding our instinctive (or motivational) needs color traits:

• Tells us how we deal with stress

• Tell us what information we need to develop trust

• Tell us how we learn

• Tell us what we need to feel secure

My client learned a great deal from her trip, and her team knows that she personally cares about each and every one on the team.

Leaders Make Personal Connections.

Influence & Insight | May 2025

Leadership Story | Leaders Engage and Motivate

Does your organization focus on motivation? Especially in large organizations, the number of administrative and other processes can seem overwhelming at times. This past month, a client shared an existing internal graphic - The Motivation Menu. It’s quite detailed and consists of twelve menu items:

Communication

Engagement

Follow-Through

Personal Growth

Impact

Empowerment

Excellence

Recognition

Flexibility

Stability

Ethics

Support

Each of the twelve categories are further detailed, so to start, we may focus on just the summary statements. The twelve appear to have much in common the the Gallup Q12 Engagement Survey questions:

Q1: I know what is expected of me at work.

Q2: I have the materials and equipment I need to do my work right.

Q3: At work, I have the opportunity to do what I do best every day.

Q4: In the last seven days, I have received recognition or praise for doing

good work.

Q5: My supervisors, or someone at work, seems to care about me as a

person.

Q6: There is someone at work who encourages my development.

Q7: At work, my opinions seem to count.

Q8: The mission or purpose of my company makes me feel my job is

important.

Q9: My associates or fellow employees are committed to doing quality work.

Q10: I have a best friend at work.

Q11: In the last six months, someone at work has talked to me about my

progress.

Q12: This last year, I have had opportunities at work to learn and grow.

Let’s look at a few areas in common. The Motivation Menu category recognition captures Gallup question 4. Motivation Menu category support captures Gallup questions 2, 6 and 11. Take a look and explore other similar threads. How does your organization learn what motivates individuals? An easy way to start is looking at your Energize2Lead (E2L) profiles.

Recall that E2L Instinctive Needs and Motivational needs are the same thing and align well with the Gallup Q12 questions as well as our client’s Motivational Menu.

Leaders Engage and Motivate.

The New CEO | Book Review

“When you're new to the CEO role, you will need to

first assess your organization's culture and then

decide what you want it to be." (p. 207)

Subtitled Lessons from CEOs on How to Start Well and Perform Quickly (minus the common mistakes) by Ty Wiggins, Ph. D. with Justus O'Brien, Laura Sanderson, Margot McShane, Rusty O'Kelley and Stephen Langton, intentionally focuses on the when and how CEOs should begin their new role (p. 10). It's worth reading Chapter 11, If I Could Do It All Over Again, first, capturing summary thoughts of numerous interviewed Chief Executive Officers. This review modestly suggests that perhaps Vison and Strategy do inform what new CEOs do, and why they do it.

In The Knowing Doing Gap, Pfeffer and Sutton significantly note (p. 22) when benchmarking other organizations, most companies:

“overestimate the importance of the tangible, specific, programmatic

aspects of what competitors, for instance, do, and underestimate the

importance of the underlying philosophy that guides what they do

and why they do it.”

Jim Collins sets up a hierarchy in BE 2.0:

and further defines Core Ideology (see Built to Last) as Purpose (Fundamental reason for existence) + Core Values (Expectations for personal behavior). Combining the two, Vision is then Core Ideology + Mission. We may also recall from Collins that an organization's purpose may change, but values are more fundamental and do not. Note that tactics follow vision and strategy.

CEO Lyssa McGowan summarizes her role:

"It was about communicating the vision for the future." (p. 45).

Wiggins' CEO Transition Success (p. 6) defines a new CEO's approach on the right, and initial priorities on the left. These ten steps outline the book.

Interestingly, the authors found when asking more than 200 CEOs globally about the things that only the CEO can or should do, they listed culture, communication, working with the board, and also vision and strategy (p. 126). Specifically, CEO Carol Tomé offers:

"I hoped to inspire around a shared purpose." (p. 153).

Two takeaways: The top regret I hear from new CEOs is that thy wish they had moved faster on their teams (p. 9). The second-most common regret from CEO, was wishing they had better engaged their board earlier (p. 9).

Approach

Humility and clarity are common to many approaches, perhaps best captured in a new CEO's Personal Leadership Philosophy, or PLP. CEO Ramon Laguarta's shares "It means you need to be curious to ensure you learn what is really happening." (p. 62) The authors seem to agree we should initially ask why:

You need to learn and to understand the business,

not look for things that confirm what you thought going in. (p. 71)

Wiggins calls out Satya Nadella, Microsoft's third CEO, who in just a little over 1,000 words, he unflinchingly set out who he was, why he was there, and what the company would do next (p. 92) -- or in essence his leadership philosophy.

Alignment is also key. One important step is to make sure you are clear about your priorities and what success looks like from the board's perspective (p. 117).

Priorities

In our Leader's Compass workshop, we stress the value of creating a leadership philosophy before we're in a leader role. If you don't leverage the time before you start, it will be harder for you to perform as fast or as well as expected (p. 36). Exactly what Carol Tomé of UPS did. What Carol did so well was to establish new and clear ground rules for how her top team would operate, almost from Day One (p. 155). She set expectations.

Sanjiv Lamba, of Linde, plc did the same: I doubled down on the communication ensuring every employee understood our priorities and why we made the decision we did (p. 42).

Numerous CEOs interviewed adopted the role of leader as coach. As CEO, your role is to create the environment where the relevant leaders with the expertise, knowledge, and understanding can help you make the best decisions (p. 167). A good performance coach understands the abilities of others and continuously aligns the team. Take time to understand individual director's views on the company, culture, top team, and opportunities, as well as what they believe the board's role is for the organization (p. 181).

CEO Doug Mack (Fanatics) "To me, being a CEO is all about being the coach of a team of elite players." (p. 135)

Summary

Marc Bitzer (Whirlpool), summarizes the approach well:

Never forget that you are here to serve. Serve the organization first,

then your team, and long afterward yourself. (p. 223)

Thank you JL Bielon, for introducing the book.

Coaching Story | Leaders Create a Motivational Environment

During a recent coaching session, a very engaging client asked how best to motivate someone when increasing salary is not an option.

Good question. Let’s recall a few things. First, according to Dan Pink (Drive), once people believe they are being paid enough, autonomy, mastery and purpose are the top three motivators in a modern, information or knowledge based environment. Second, consider the Application and Action from our Creating a Motivational Environment workshop:

1. Do leaders motivate people?

2. What are some non-financial forms of compensation with which you may use to help motivate employees?

3. What are the five (5) factors that most motivate you (in order of priority)?

4. Which of the factors cited in #2 above, are present in your current job?

5. List three of your direct reports and indicate the factors that you think motivate them

Note: you should meet with each at some point to confirm your assumption

6. How are you ensuring that you are establishing the right conditions for motivating the three direct reports above?

Offering schedule flexibility (autonomy), training opportunities (mastery), and sharing a leadership philosophy aligned with one’s organization (purpose) are great ways to address non-financial forms of compensation. Number five on the form is a reminder that serving as a coach, or knowing what actually motivates our direct reports, is vital. Numbers 1 and 6 are related in that rather than believe we can actually motivate someone, perhaps we should focus on creating the environment where individuals and teams will thrive, or become intrinsically motivated.

My client and I explored these concepts and she came up with some great ideas for her team.

Leaders Create a Motivational Environment.

Influence & Insight | April 2025

Leadership Story | Leaders Look Forward

There’s a lot of anxiety today about Artificial Intelligence (AI), especially the possibility of AI technology replacing jobs. It’s worth exploring from a leadership perspective. In our Academy Leadership Setting Leadership Priorities Workshop, we discuss the difference between effective and efficient, defining:

Efficient: Doing things right.

Effective: Doing the right things and doing them in order of priority.

Workshop audiences quickly conclude that focus on efficiency is the domain of the manager and that focus on effectiveness is the domain of the leader. Often during the session we recall the fate of organizations that seemed to focus on the former rather than the latter with devastating results. Companies such as Blockbuster Video, Kodak, Nortel Networks and others come to mind.

During a recent graduation ceremony for a senior leader team, lers of a county information technology team, a couple members shared emerging job descriptions, now in very high demand, for those who understand and effectively use emerging AI Tools such as ChatGPT and others. It was an illuminating discussion and the challenge for me was attempting to remember the new job description names which are quickly becoming ubiquitous.

The discussion and subsequent newly identified jobs are very similar to what Jim Clifton and Jim Harter describe in the Future of Work section of It’s The Manager. One key finding: An Accenture global study of 1,000 large companies identified three categories of jobs that AI will create (p. 177):

• Trainers: those who need to teach AI systems how to interpret interactions and perspectives.

• Explainers: those who interpret AI to make it contextually useful in making decisions.

• Sustainers: those who evaluate the ethical and performance characteristics of AI.

The new job descriptions the county leaders were talking about sounded a lot like trainers, explainers and sustainers. More importantly, the discussion was validating that a focus on effectiveness remains in demand today, while a focus on efficiency (think word search) may easily be replaced by a sophisticated AI engine. Just as Setting Leadership Priorities workshop participants discover that effectiveness often centers around leading people, Gallup authors have concluded:

The most important jobs of the future will require social skills, and human interactions

will remain the most powerful way to build relationships with customers. (p. 179)

Leaders Look Forward.

It's The Manager | Book Review

“The old boss-to-employee, command and control leadership environment has "worked" when it comes to building process efficiency systems, engineering large buildings and creating infrastructure. But the top-down leadership techniques of the past have not adapted to a workplace that now demands coaching and collaboration to thrive" (p. 1)

Jim Clifton & Jim Harter's first of their three book series published between 2019 and 2023, subtitled Moving From Boss to Coach, explains the why and the how current and aspiring leaders should be coaches rather than traditional, authoritative bosses. Although this work was written pre-Covid, contemporary Gallup findings in the author's third book in the series, Culture Shock, validate if not amplify 2019 observations, in particular with regard to employee engagement. This review explains the why, or corporate engagement findings and offers suggestions regarding how -- by examining the two larger Boss to Coach and The Future of Work sections.

Landscape

Consider relatively flat individual employee engagement numbers which have hovered around 30% for decades. The authors recommend a simple, yet breakthrough goal for any leader or human resources department. If, of your managers, 30% are great, 20% are lousy and 50% are just there -- which are about the U.S. national averages of employee engagement -- double the 30% to 60% and cut the 20% to single digits. Do this and your stock price will boom (p. 14).

How might one start this process? Perhaps we should rely less on, but not abandon process-oriented results driven corporate metrics and increase focus on individual personal development. Matt Lieberman's findings, published in Harvard Business Review, found that focusing on both people and results increases sixfold how frequently we are viewed as great leaders.

Take a look at the changing demands of the workplace (p. 21), similarly described in multi-generational works such as Gentelligence or What Millennials Want From Work:

Past Future

My Paycheck

My Satisfaction

My Boss

My Annual Review

My Weaknesses

My Job

My Purpose

My Development

My Coach

My Ongoing Conversations

My Strengths

My Life

It's tempting to proclaim we're casualties of matrixed working environments. Yet how connected your teams of managers are as a group will determine whether the teams they manage will support other teams or not (p. 27). Stanley McChrystal found and describes the same in Team of Teams. We should foster knowledge-sharing and informal communication channels between teams in addition to increasing personalized individual development plans.

Boss to Coach

If leaders were to prioritize one action, Gallup recommends that

they equip their managers to become coaches. (p. 89)

This finding mirrors the Culture Shock recommendation:

Make sure your managers hold one meaningful

conversation per week with each employee.

That's the conclusion, and the authors answer to how is called Moneyball for workplaces, essentially the Gallup Q12 Engagement Survey Questions (p. 109):

Q1: I know what is expected of me at work.

Q2: I have the materials and equipment I need to do my work right.

Q3: At work, I have the opportunity to do what I do best every day.

Q4: In the last seven days, I have received recognition or praise for doing good work.

Q5: My supervisors, or someone at work, seems to care about me as a person.

Q6: There is someone at work who encourages my development.

Q7: At work, my opinions seem to count.

Q8: The mission or purpose of my company makes me feel my job is important.

Q9: My associates or fellow employees are committed to doing quality work.

Q10: I have a best friend at work.

Q11: In the last six months, someone at work has talked to me about my progress.

Q12: This last year, I have had opportunities at work to learn and grow.

Besides a deliberate shift to leader as coach, much of the Q12 seems to hint at creating a motivational environment. Think about the Motivational Assessment from an Academy Leadership Creating a Motivational Environment workshop, spanning the discovery of what motivates or demotivates someone to identifying personal dreams and goals, foundational steps for any coach. It's difficult to underestimate the influence a single supervisor or manager may have:

One of Gallup's biggest discoveries is: The manager or team leader

alone accounts for 70% of the variance in team engagement. (p. 114)

Here are additional tips on how to refocus our energies. The five traits of Great Managers (p. 126):

1. Motivation - inspiring teams to get exceptional work done

2. Workstyle - setting goals and arranging resources for the team to excel

3. Initiation - influencing others to act, pushing through adversity and resistance

4. Collaboration - building committed teams with deep bonds

5. Thought process - taking an analytical approach to strategy and decision-making

Future of Work

Return to Office remains a dominant workplace topic, even in our post-Covid era. That's probably because the most desired perk is workplace flexibility (p. 135). Employees are watching closely whether or not organizations "walk the talk" regarding work/life balance:

Whether an organization offers flexibility and whether it

actually honors flexibility are two different things. (p. 152)

Recall the Changing Demands of the Workplace or focus on my life rather than my job. The authors share the key to accommodating female employees to your organization is making your workplace culture flexible enough to accommodate family and life obligations (p. 151). It may very well be that women increasingly entering the workplace has spearheaded a focus on work-life balance. Maybe women are leading the way since the majority of Americans now report virtually no difference in gender preference for a boss (p. 145).

A couple other nuggets:

Keep in mind the ultimate outcome of flexible work: autonomy with accountability (p. 161). The formation of effective teams, especially those where individuals know and hold each other to high standards is paramount.

Beware of administrative leadership. Diversity training often fails when it feels mandated and is not part of a culture built on respect, strengths and leadership commitment (p. 138). Culture, not fads, matter.

Baby boomers have shown a greater desire than workers in other generations to develop their colleagues, and they often outpace younger workers in their capacity to build a business (p. 155). They are at a stage in life where they are natural coaches.

Employees in the workforce aren't looking for amenities such as game rooms, free food and fancy latte machines. But they are looking for greater flexibility, autonomy and the ability to lead a better life (p. 157). We should focus on what is meaningful.

Summary

Gallup's considerable data on engagement and recommendation to double it are a fantastic starting point for any manager who wishes to lead. Remember, becoming a leader is not about us.

Perhaps the most salient point is that

each individual employee -- women as well as men --

defines what a good life and career means for them. (p. 153)

Team Gallup generously provided a copy of the book for review.

Coaching Story | Leaders Develop Others by Listening

Delegation remains one of the most common listed Action Plan Leadership Behaviors I Will Change in the Next 90 Days following an Academy Leadership Excellence Course (LEC), particularly for the most proficient Subject Matter Experts (SMEs).

Let’s review the following Feedback Profiles, originally shared in 2020:

We can equate evaluation with talking or telling others what to do and coaching with listening and supporting. Discussing the two feedback profiles often has a lasting effect, especially on SMEs. Not surprisingly, during initial follow-on LEC coaching sessions, the desire to grow into the Leader as Coach role surfaces, but often with a challenge:

How do I start?

A common theme to virtually all of these coaching sessions is the initial presumption the SME/Manager has to figure out what is best for their subordinates, or what may be delegated to direct reports, all by themselves. It’s an unnecessary trap and seems a symptom of a lifetime of focus on individual professional accomplishment.

In our Coaching to Develop People workshop, we discover that in order to be an effective [leader as] coach, leaders must thoroughly understand the abilities, limitations, potential and professional goals of their people. Or put another way, we’re not going to figure these things out all by ourselves. In at least two coaching sessions this past month, we came up with the idea of supervisors and subordinates sharing motivation assessments and Energize2Lead Profiles (if available) in a one-on-one session. As the leader learns more about what motivates the subordinate and what things they like to do (preferred E2L dimension or top colors), both a development plan and candidate delegation task emerge, primarily formed by the subordinate.

Interestingly, this is the final takeaway in the book review of It’s The Manager — Let the employees tell you what they want - it’s not about us.

Leaders Develop Others by Listening.

Influence & Insight | March 2025

Leadership Story | Make Your Leadership Philosophy Personal

Every now and then, we’re encounter something completely out of the box, unique and exciting. Sometimes we encounter a Personal Leadership Philosophy (PLP) telling a compelling lifetime story, or composed with very inspiring words.

A recent Leadership Excellence Course graduate composed her PLP as a dashboard, in Tableau Reader software. Not surprisingly, she strives to have a creative, fun, and empowering environment. Her commitments, likes, dislikes and non-negotiables may be viewed by hovering over the respective icons on the visual dashboard.

The first of three listed values listed is creativity. Priorities are visually displayed, top to bottom, as horizontal bars, with the top priority the longest, and in the darkest color hue.

It’s a work of art. It’s out of the box. It’s simply terrific. It’s authentic.

Make Your Leadership Philosophy Personal.

Don't Sweat The Small Stuff | Book Review

“We overreact, blow things out of proportion, hold on too tightly,

and focus on the negative aspects of life." (p. 1)

Dr. Richard Carlson's one hundred brief and simple chapters seemingly fall into categories that naturally align with multiple Academy Leadership Excellence Course (LEC) workshops: Setting Leadership Priorities, The Leader's Compass, and Energize2Lead (E2L). An additional category, Gratitude, is worth establishing as empathy, meaningfulness and compassion have increasingly emerged as leadership themes in recent LECs.

Priorities

Stephen Covey's four quadrants inform us Quadrant II is where opportunity forms and that we should spend more time performing such activities, rather than reacting to Quadrant I events. Consider expanding Quadrant II holistically, including activities such as exercise. Carlson seem to think this way too. You might become an early riser, for example, and spend one hour that is reserved for reading, praying, reflecting, meditating, your exercise, or however you want to use the time (p. 244).

Likewise, everyday small successes may become both habits and eventually, larger successes. All we really have to do is focus on those little acts of kindness, things we can do right now (p. 201). It's also a lot more fun. We take our own goals so seriously that we forget to have fun along the way, and we forget to cut ourselves some slack (p. 62).

Leader's Compass | High Performance

Toward the end of our Leader's Compass workshop, we learn energy is the fundamental currency of high performance.

Consider a corporate culture or boss demanding we always be on, 24/7. In such an environment, one is likely toggling between the upper two quadrants.

Much of our anxiety and inner struggle stems from our busy, overactive minds always needing something to entertain them, something to focus on, and always wondering "What's next?" (p. 50). We could call this a Professionally Busy mindset.

Tony Schwartz, co-author of The Power of Full Engagement, recommends redirecting activities to the right two quadrants. Carlson enthusiastically recommends activities in the lower right quadrant. Whether it's ten minutes of meditation or yoga, spending a little time in nature, or locking the bathroom door and taking a ten-minute bath, quiet time to yourself is a vital part of life (p. 69). Imagine redirecting from the upper left to the lower right quadrants. The next time you're feeling bad, rather than fight it, try to relax (p. 140).

We all get angry or otherwise find ourselves in a highly negative state from time to time. When it comes to dealing with negative thoughts, you can analyze your thoughts, or you can learn to ignore them (p. 165). Remind yourself that it's your thinking that is negative, not your life (p. 228).

Personal Energy (E2L)

Recall the three dimensions of our E2L profile; preferred, expectations and instinctive. When our activities (or jobs) don’t align with our preferred colors, our stress level rises and if our expectations (colors) are not met, we're now in instinctive mode consuming vast amounts of energy.

What you want to start doing is noticing your stress early before it gets out of hand (p. 54). Frequently, our right-brain traits (or yellow and blue colors) fade away under stress. Fearful, frantic thinking takes an enormous amount of energy and drains the creativity and motivation from our lives (p. 11).

Our E2L workshops demonstrate that 75% of people are wired differently than us and learning more about our expectations profiles help us approach each other according to our differences. I encourage you to consider deeply and respect the fact that we are all very different (p. 114).

Gratitude

Carlson repeatedly advises different forms of gratitude, and we may think of gratitude as the intersection between priorities, a leadership philosophy and our strongest personal energy source. Compassion develops your sense of gratitude by taking your attention off all the little things that most of us have learned to take too seriously (p. 18). We should cultivate gratitude as a lifetime habit. The point is to gear your attention toward gratitude, preferably first thing in the morning (p. 66).

Consider the opposite: Continuous, negative evaluation. Carlson calls this weatherproofing. Essentially, weatherproofing means that you are on the careful lookout for what needs to be fixed or repaired (p. 105).

Summary

Carlson reveals his own values. Each act of kindness rewards you with positive feelings and reminds you of the important aspects of life -- service, kindness, and love (p. 90).

"I've yet to meet an absolute perfectionist whose life

was filled with inner peace." (p. 9)

Coaching Story | Leaders Create a Cultural Oasis

Recall Karin Hurt & David Dye’s Courageous Cultures 2021 book review, introducing a Cultural Oasis as the solution when wondering if it still possible to build a Courageous Culture on my team within unsupportive or toxic environments. Here’s a theory: Post-Covid, many employees Returning to Office (not work) immediately notice a reduction in autonomy, work-life balance, and subsequent motivation. Likely added compliance. This is one of the most common discussion points in leadership courses the past two years.

As a result, many don’t want to speak up or believe they can make a difference. Hurt and Dye remind us we can all relate to unsafe meetings or a work environment where the Fear of Speaking Up (FOSU) exists.

As a countermeasure, three helpful cultural characters are offered:

• Microinnovator The employee who consistently seeks out small but powerful ways to improve the business.

• Problem Solver The employee who cares about what’s not working and wants to make it better.

• Customer Advocate The employee who sees through your customers’ eyes and speaks up on their behalf.

Let’s encourage collaboration upon returning to the office, perhaps requesting volunteers for the three cultural roles above.

Leaders Create a Cultural Oasis.

Influence & Insight | February 2025